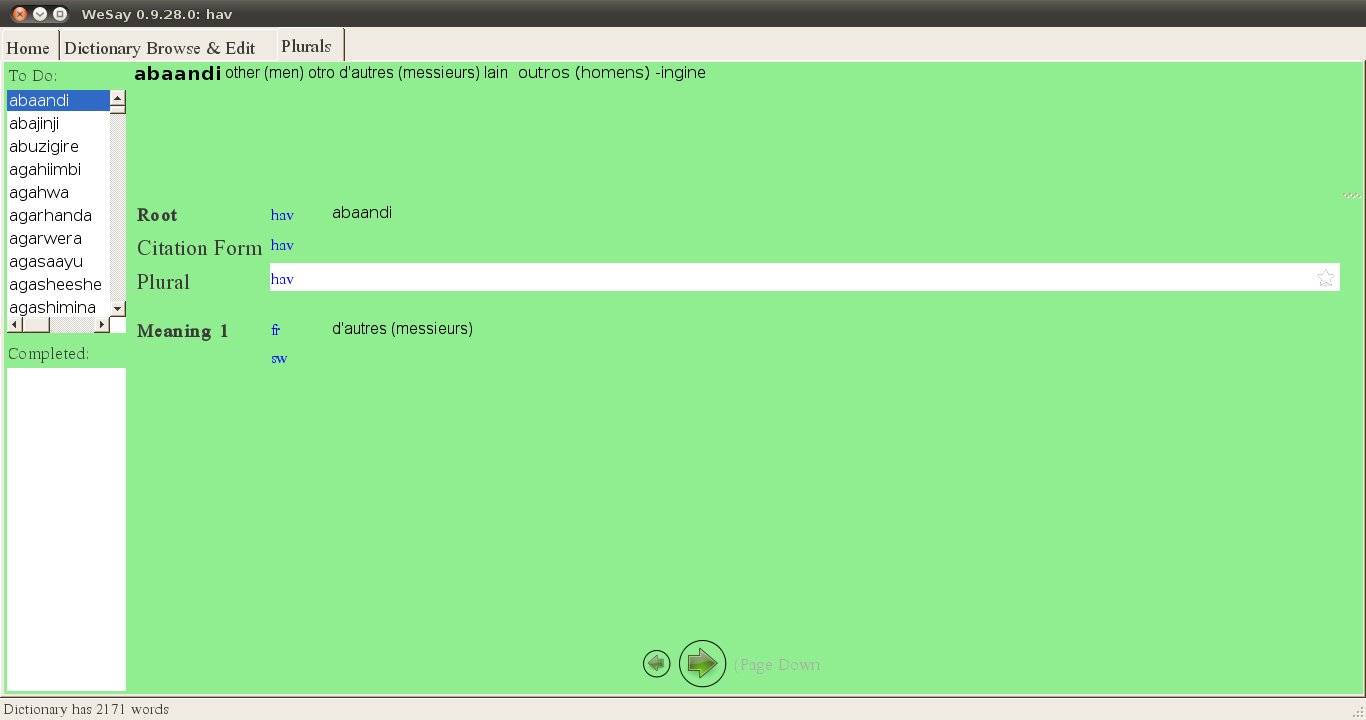

I’ve written before about using WeSay to collect language data, and Wesay lift files can be fairly easily imported into Fieldworks Language Explorer (FLEx) for analysis. Recently, I’ve been working on getting data from the FLEx lexicon into XLingpaper, to facilitate the writing of reports and papers than can be full of data (which is the way I like them…:-)).

I start with a lexicon (basically just a word list) in flex, that has been parsed for root forms (go through noun class categorization and obligatory morphology with a speaker of the language). Figure out the canonical root syllable profile (e.g., around here, usually CVCV), and look for complimentary distribution and contrast within that type, both (though separately) for nouns and verbs.

I have a script that is putting out regular expressions based on what graphs we expect to use (those in Swahili, plus those we have added to orthographies in the past –since we start with data encoded in the Swahili/Lingala orthography, this covers most of the data that we work with). This script puts out expressions like

^bu([mn]{0,1})([[ptjfvmlryh]|[bdgkcsznw][hpby]{0,1}])([aiɨuʉeɛoɔʌ]{1,2})([́̀̌̂]{0,1})$

which means that the whole word/lexeme form (between ^ and $) is just b, u, some consonant (one of m or n, or not, then a consonant letter that appears alone, or the first and second of a digraph), then some vowel (any of ten basic ones, long or short, plus diacritics, or not). In other notation, It is giving buCV, or canonical structures with root initial [bu]. This data is paired with data from other regular expression filters giving [b] before other vowels to show a complete distribution of [b] before all vowels (presumably…).

The script puts out another expression,

^([mn]{0,1})([[ptjfvmlryh]|[bdkgcsznw][hpby]{0,1}])(a)([mn]{0,1})([[ptjfvmlryh]|[bdkgcsznw][hpby]{0,1}])3([́̀̌̂]{0,1})$

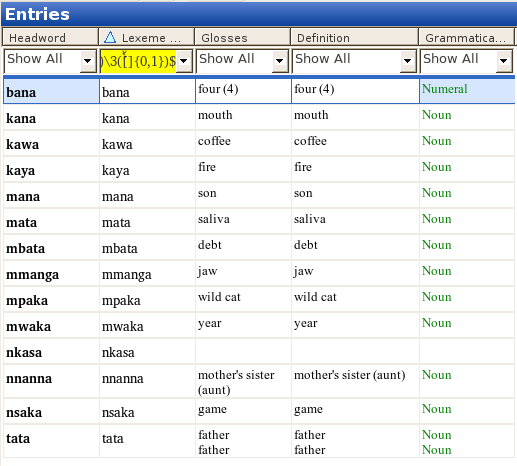

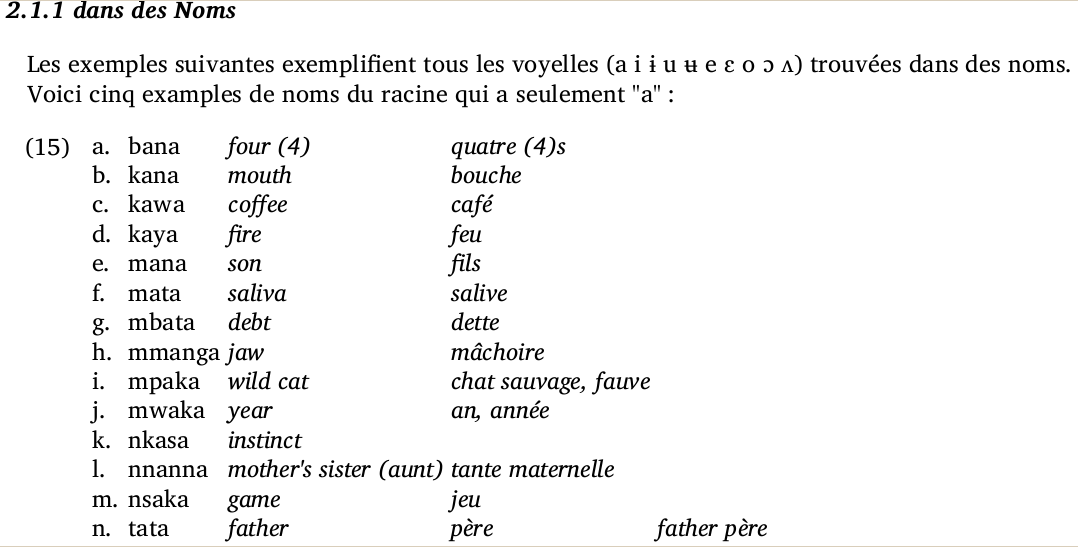

which gives me CaCa, as in the following screenshot:

(The 3 refers to the third set of parentheses, (a), so that changing (a) to (i) gives you CiCi.) The data from these filters gives evidence of the independent identity of a vowel, as opposed to vowels created through harmony rules.

So these regular expressions allow filtering of data in the FLEx lexicon to show just the data that you I need to prove a particular point you’re trying to make (in my case, why just these letters should be in the alphabet). But then, how to get the data out of FLEx, and into a document you’re writing?

FLEx has a number of export options out of the box, but none of them seem designed for outputting words with their glosses, based on a particular filter/sort of the lexicon. In particular, I’m looking for export into a format that can be validated against an XLingpaper DTD, since I use XLingpaper XML for most of my writing, both for archivability and longevity of my data, as well as for cross-compatibility in differing environments (there are also developed stylesheets to make XLingpaper docs into html, pdf, and usually word processor docs, too). The basic XML export of the data on the above sort starts like this:

<?xml version=”1.0″ encoding=”utf-8″?>

<ExportedDictionary>

<LexEntry id=”hvo16380″>

<LexEntry_HeadWord>

<AStr ws=”gey”>

<Run ws=”gey”>bana</Run>

</AStr>

</LexEntry_HeadWord>

<LexEntry_Senses>

<LexSense number=”1″ id=”hvo16382″>

<MoMorphSynAnalysisLink_MLPartOfSpeech>

<AStr ws=”en”>

<Run ws=”en”>num</Run>

</AStr>

</MoMorphSynAnalysisLink_MLPartOfSpeech>

<LexSense_Definition>

<AStr ws=”en”>

<Run ws=”en”>four (4)</Run>

</AStr>

</LexSense_Definition>

<LexSense_Definition>

<AStr ws=”fr”>

<Run ws=”fr”>quatre (4)s</Run>

</AStr>

</LexSense_Definition>

<LexSense_Definition>

<AStr ws=”swh”>

<Run ws=”swh”>nne</Run>

</AStr>

</LexSense_Definition>

<LexSense_Definition>

<AStr ws=”pt”>

<Run ws=”pt”>quatro (4)</Run>

</AStr>

</LexSense_Definition>

<LexSense_Definition>

<AStr ws=”es”>

<Run ws=”es”>cuatro</Run>

</AStr>

</LexSense_Definition>

</LexSense>

</LexEntry_Senses>

</LexEntry>

<LexEntry id=”hvo11542″>

<LexEntry_HeadWord>… and so on…

But this is way more information than I need (I got most of these glosses for free using the CAWL to elicit the data), and in the wrong form. The cool thing about XML is that you can take structured information and put in in another structure/form, to get the form you need. To do this, I needed to look (again) and xsl, the extensible stylesheet language, which had succesfully intimidated me a number of times already. But with a little time, energy, and despration, I got a working stylesheet. And with some help from Andy Black, I made it simpler and more straightforward, so that it looks like XLPMultipleFormGlosses.xsl looks today. Put it, and an xml file describing it, into /usr/share/fieldworks/Language Explorer/Export Templates, and this is now a new export process from within FLEx. To see the power of this stylesheet, the above data is now exported from FLEx as

<?xml version=”1.0″ encoding=”utf-8″?>

<!DOCTYPE xlingpaper PUBLIC “-//XMLmind//DTD XLingPap//EN” “XLingPap.dtd”>

<xlingpaper version=”2.8.0″>

<lingPaper>

<section1 id=”DontCopyThisSection”>

<secTitle>Click the [+] on the left, copy the example that appears below, then paste it into your XLingpaper document wherever an example in allowed.</secTitle>

<example num=”examples-hvo16380″>

<listWord letter=”hvo16380″>

<langData lang=”gey”>bana</langData>

<gloss lang=”en”>four (4)</gloss>

<gloss lang=”fr”>quatre (4)s</gloss>

</listWord>

<listWord letter=”hvo11542″>

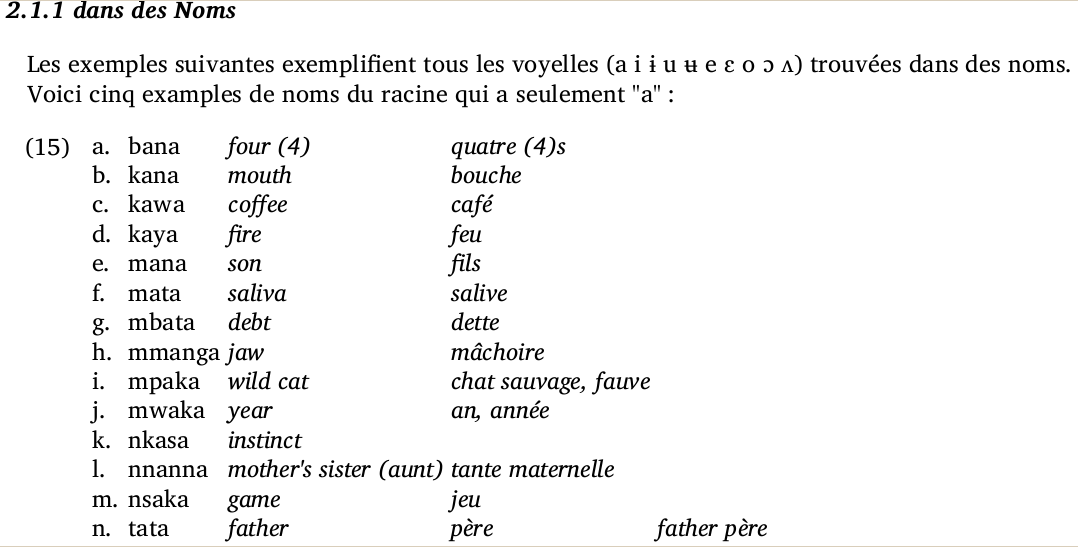

which contains just enough header/footer to validate against the XLingpaper DTD (so you don’t get errors opening it in XMLmind), and the word forms and just the glosses I want (English and French, but that is easily customizable in the stylesheet). The example node can be copied and pasted into an existing XLingpaper document, which then can eventually be transformed into other formats, like the pdf from this screenshot:

which I think is a pretty cool thing to be able to do, and an advance for the documentation of languages we are working with.