I think it would be helpful to language communities to have an orthography development/checker tool in WeSay. For why I think that and what I’d want to do with it, see this other post. Here’s what I would like to see:

Config:Verification

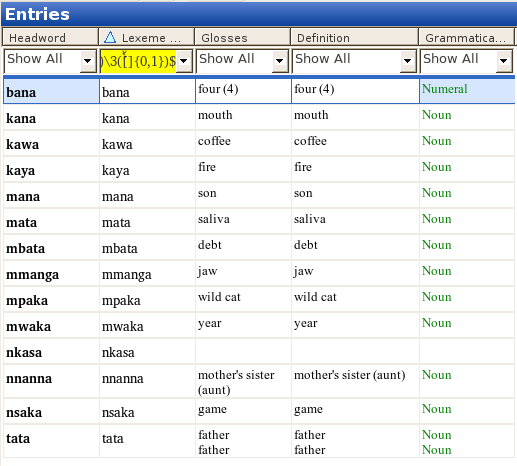

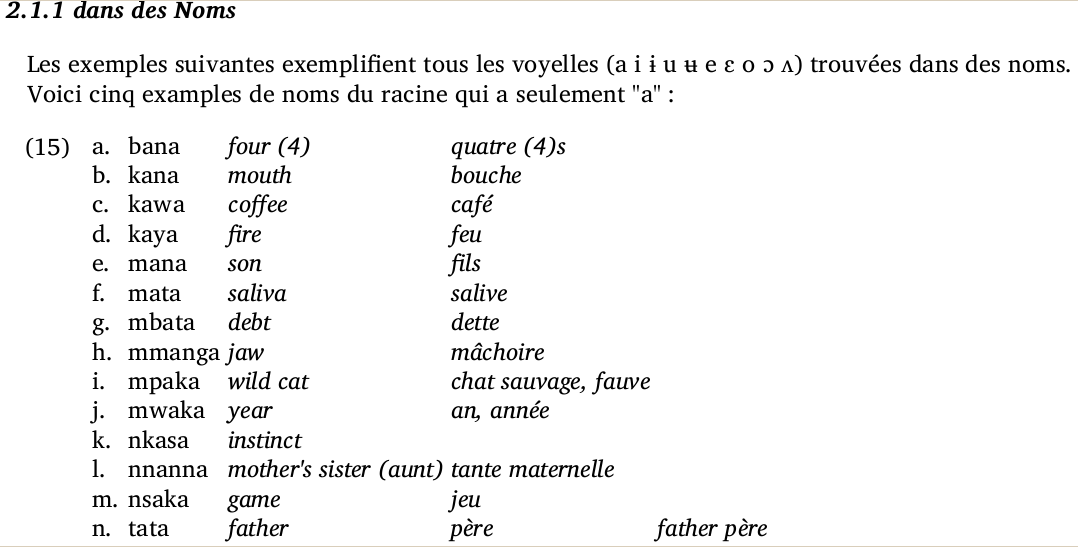

Making the task simple for the user will necessarily require other complexities. We would need a config page, that would specify which words we’re looking for. It would basically be a filter for

1. Part of speech (maybe just from a list of noun, verb, and other)

2. Syllable type (e.g., px-CVCV, px-CVC, etc. –I’m not sure how hard this would be)

2b. position in the root: (C1, C2, V1, V2)

3. Consonants [] or Vowels [] (we just look at one or the other at a time)

4. Consonants available (for later selection by user)

5. Vowels available (for later selection by user)

6. Syllable types available (Options to choose from for dropdown in #2. For ortho development, this could contain just one or two canonical types; for full dictionary checking it would require more. I’m not sure how savvy WeSay could be at this point. It might be wise to split this into two groups, one for nouns, and another for verbs –or more.)

Based on the above information, the user is asked which letter to verify, and then would be presented with a “Verification” page where he would decide whether the sound in the position in question on each word is the same (or not) as others that are marked with the same letter (in the same position of the same types of words).

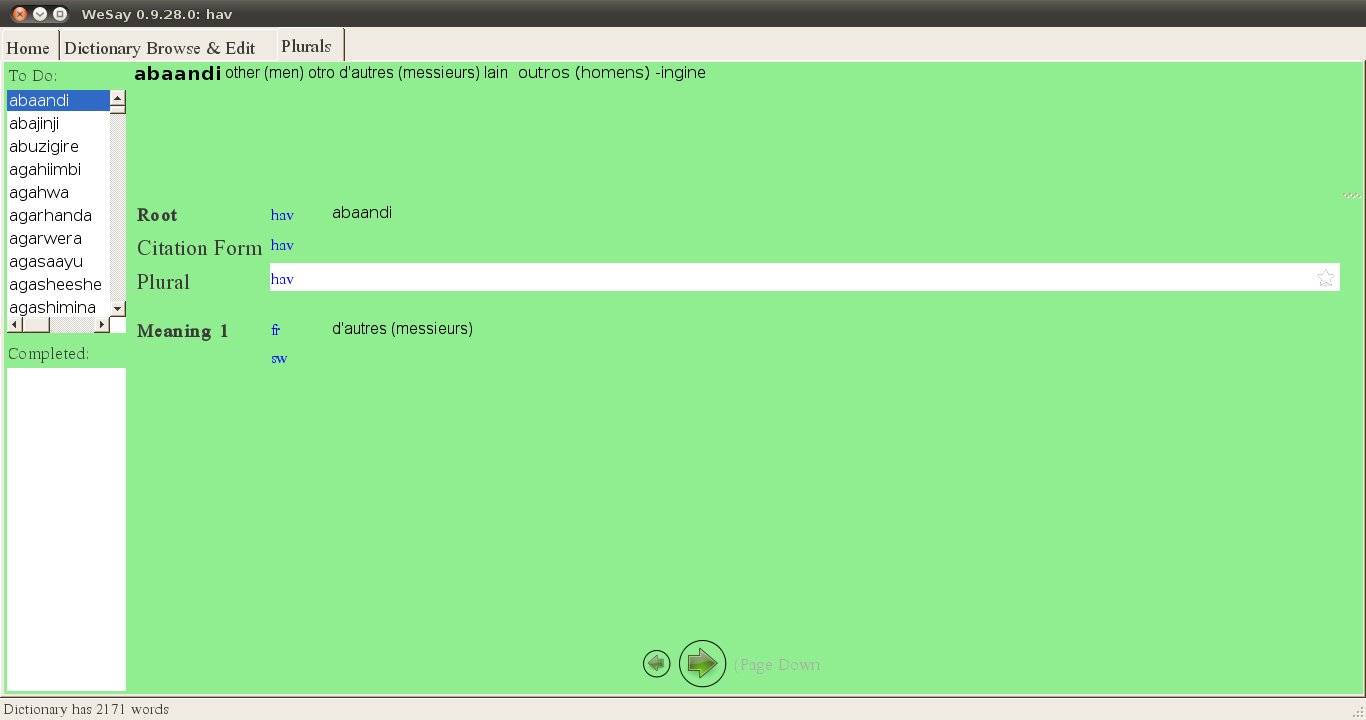

Verification

At the top of the page would be a new word, with LWC glosses and a picture, if available, and a list of words below it (all of which are filtered according to the settings on the config page, so we’re only looking at sounds/letters in one part of the same type of word) If it were simple to bold the letter in question in each word, that would be great, but not necessary to the task. In any case, it would be good to prominently display the letter under investigation, and more (very?) subtly the part of speech, syllable profile and root position. At the top of the page are two buttons: “Yes” and “No,” and at the bottom of the page are “Recheck” and “Verification OK/Next Letter”

The user task is to understand and pronounce the word at the top of the page, and decide if it belongs with the rest. If it does, he clicks “Yes”; otherwise, “No.” Once a button is clicked, another word is presented (If a mistake is made it will be sorted out later). Once the user has gone through all the input words and he is satisfied that the list of words all belong in the same group (if he isn’t sure, “Recheck” would redo the list –with just the “Yes” words), he clicks “Verification OK/Next Letter” and the following is done behind the scenes:

1. the letter (e.g., ‘p’, ‘b’, or ‘f’) in the place in question (e.g., first consonant) is changed to the letter being verified (e.g., ‘p’) for each word on the “Yes” list, if it isn’t already that letter.

2. those words are marked as verified for that letter (Is this possible? We could track progress elsewhere, if need be).

The user is then returned to the dialogue asking which letter to compare (next, and given the option to quit/pause). The same page is presented, but with words that had been taken out of the last group (i.e., “No” was clicked) along with words with the new letter, and the process repeats. If at any time the user terminates the task, it would be nice if the words that had been put in a box they might not belong in (i.e., marked “No” to ‘p,’ but not “Yes” to anything else yet) could be marked as unverified orthography (for that letter?). Then, when this task is started up again, it can start where it was left off.

At any point the user says, “give me the words with letter ‘x’,” he will get words that have been verified, and words that didn’t belong somewhere else (unless there were no “No” words on the last run). Thus, if there is a word that was wrongly put into a group (bad user input), a letter can always be re-verified (One can go back and click “No” on a word that one had just accidentally clicked “Yes” on). In any case, a spelling/letter is not corrected without comparing it to a list of words using the same letter in the same place of the same type of word. (I’m presuming good/new/consistent orthographies here, not ones like English, where a list of correctly spelled words would be more appropriate.)

Occasionally the process would need to be stopped to modify words that had been wrongly indicated for part of speech, root or syllable profile –unless the user doesn’t mind continually hitting “No,” or there is some other way of excluding them from the sort (maybe “Yes,” “No,” and “Wrong Category”?)

Once all the letters have been gone through for a given syllable type/position and part of speech, the settings on the config page could be changed, and the next set of words could be begun. If we put all but the letter to investigate on a hidden config page, then this would be just a one page task. Getting through all the letters in a given position can take awhile, so changes to those config settings (other than the letter to verify) wouldn’t need to be done all that often.

I originally had a “sorting” page before the verification page, since that is the way we do it with cards, but I think we could use a simple binary sort, as is present in the “verification” page, from the beginning. With cards on a table, a given sort might come up with a number of different piles (i.e., if there were m’s, f’s, and ɸ’s mixed up with p’s and b’s, for some reason. Or more likely, if there was under-differentiated vowels, and five vowels become nine.) But I think in either case, a binary sort would do, it would just take a bit longer (a few more sorts) to get each record in it’s proper pile.

Feasibility

I’m not sure how feasible this idea is; it is probably more like a “purple elephant” wish, but it would be nice to have, if possible. Without any real knowledge of the inner workings of WeSay, I imagine that knowledge of CV structure might be the largest hurdle to this idea’s implimentation. Normally when I collect words, I collect a couple forms: sg/pl for nouns, and infinitive/imperative for verbs, or whatever two forms will give me root structure information (a bit of preliminary research may be necessary to know what will work/help). While I can add fields for plural, infinitive and root in WeSay, there is no task to “add forms”, so giving WeSay information on syllable structure would be a more consultant-oriented task, using “Dictionary Browse and Edit”. Unless we had “Add forms: plural” and “Add forms: imperative” and then “Add Root forms”:

Add forms: plural:

word:

plural:

Add forms: imperative:

word:

imperative:

Add Root forms:

(in config:

noun root parsing fields to compare:

[ ] and

[ ]

verb root parsing fields to compare:

[ ] and

[ ])

field 1:

field 2:

root: (this might even be guessable?)

But there are probably other hurdles that I would be completely unaware of. Anyway, this is my idea.

EDIT:

Actually, looking back at our proceedures, we would like an ability to filte on words with V1=V2 (at least), and also C1=C2, if possible.

Then normally we would look at all vowels in V2 position with V1=a (for instance), then V1=i, etc.

This makes the investivation process much more straightforward (paka is more clearly ‘a’ than paki), though perhaps it would impossibly complicate the innards of the task, were they ever doable.